January 5, 2015—Marian Smith, professor of musicology and music history, tells us about unearthing forgotten choreography, and about how her work earned a mention in The New York Times.

The revival of Paquita at the center of Smith’s recent work is scheduled for a free, live webcast on Sunday, January 11, 2015 at 9 a.m. PST.

What basic questions does your current project seek to answer?

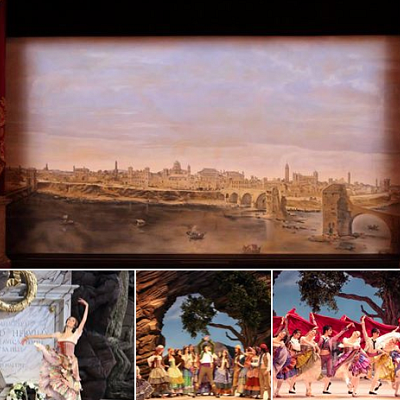

The project is a historically-informed reconstruction of the ballet Paquita, which was created in Russia in 1881 by the great French choreographer Marius Petipa (and based on an earlier version by his predecessor Joseph Mazilier in Paris in 1846). By "historically informed" I simply mean that it is based on historical sources and is intended to reproduce the nineteenth-century Russian production as closely as possible.

The really, really basic question behind the work is: what did this ballet look like in its original incarnation? Watching this revival is like going back in a time machine and seeing ballet of the golden age in Imperial Russia. Incredible.

The revival premiered at the State Opera House in Munich on December 13, 2014, performed by the Bavarian State Ballet. The company directors Ivan Liška and Wolfgang Oberender were tremendously supportive of this whole project. It was a big success and received excellent reviews, including in The New York Times and in many German newspapers.

What was your role in the reconstruction?

I consulted with choreographer Alexei Ratmansky about how the mime scenes are coordinated with the music. Almost half of this ballet consists of mime scenes—that was normal for many nineteenth-century ballets. But over the years a lot of those mime scenes have disappeared from the ballets.

Why is it important for audiences to see a ballet as it was originally choreographed?

Well, it's sort of like the early music movement. By restoring the mime scenes and the choreography that comprised the original Paquita, we in the audience can find beautiful and interesting qualities in this ballet that we otherwise miss. The story and characterizations are stronger. You have a deeper, more thrilling experience.

Why is it important for dancers to dance a ballet as it was originally choreographed?

It's time for a revolution in classical dance performance, just like we've had in classical music performance. Dancers can profit from learning both the mime and the dancing in this nineteenth-century style. Mime is fundamental for communicating and creating character. The Petipa dance style is amazing—so subtle, so rich. There are so many positions of the head and the eyes; so many ways the shoulders can relate to the head and the arms and the legs. It almost reminded me of Balinese classical dance, in that so many things are happening in the body at once, yet whe it's done well it creates the effect of an organic whole.

What has it been like working with the esteemed Alexei Ratmansky?

It has been a fantastic experience, and I have learned a lot from it. He is very focused, very non-egotistical guy, who is extremely knowledgeable. He is also deeply curious about ballet history, and has collected hundreds of photographs and images from Petipa productions that were very useful. He has so much respect for the great artists of the past.

How is the UO supportive of your scholarship?

The UO has supported my scholarship in many ways. Three times in my career, I have been able to take a term off from teaching and work on my own research at the Oregon Humanities Center, which offers excellent support for faculty research. SOMD Dean Brad Foley has generously supported as much as he possibly can, including funding annual trips to meetings of the American Musicology Society, which is absolutely vital for scholars who want to toss around new ideas.

I also have wonderful colleagues and graduate students here at the UO; being a part of a lively, active research community is crucial.